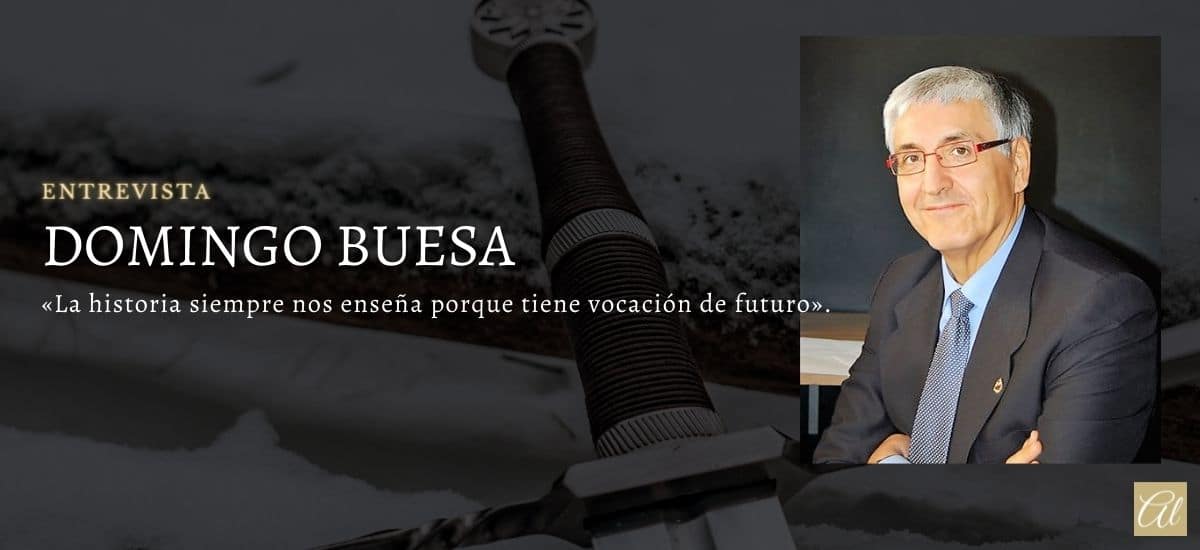

Cover photo, courtesy of Domingo Buesa.

Sunday Buesa has a long history in the teaching and dissemination of History by vocation and work. With more than 60 published books, this historian also writes novels and The afternoon that Zaragoza burned is his last title. Thank you very much for giving me your time for this interview, the first of this new year, where he tells us a little about everything.

Domingo Buesa - Interview

- ACTUALIDAD LITERATURA: You are a historian with more than 60 published books. How was the jump to the novel?

DOMINGO BUESA: For two years, the editor Javier Lafuente asked me to write a novel for him to include in the collection The History of Aragon in Novel, edited by Doce Robles. In the end, I promised that I would try but that I was not convinced that I could fulfill the orderBecause he had never done a novel and, furthermore, he had enormous respect for this exciting way of bringing history closer to society.

I remember that summer I began to write a novel on a subject whose documentation I had studied extensively and even published. And here the great surprise arose: not only was it possible for me to do it, but it also gave me enormous satisfaction. I was happy writing that story about a true story, the hours passed without feeling and the event of 1634 acquired life and vitality in that environment of my library. The characters appeared on my computer and, after a while, they ended up taking me where they considered. What was augured as an ordeal had become a passion. Had been born They will take Jaca at dawn.

- AL: The afternoon that Zaragoza burned It is the second novel you have. What do you tell us about it and where did the idea come from?

DB: The success of the first novel led us to consider, with my editor, the realization of a second installment. And again the subject was suggested by me, since I understand that you must novelize those themes and spaces of history that you know well. In this case I was passionate about the figure of Ramón Pignatelli, the great illustrated Zaragoza, and in that environment the Bread Uprising had been experienced, brutally put down in 1766 by the bucklers. The key to understanding how this novel came to be considered is to be found in the two years of work that it takes me to mount a large exhibition on the Zaragoza of the Enlightenment, entitled Passion for Freedom. And that tells the novel, the passion for progress of enlightened people that they have to live the uprising of a people that has no bread and that can hardly pay the high rents.

- AL: Can you go back to that first book you read? And the first story you wrote?

DB: From a very young age I have really liked reading, I think it is fundamental and that it is the basis of any personal project. The first book I remember reading is a children's edition of Lazarillo de Tormes, which my dear uncle Teodoro, my grandfather's brother, gave me. That was a discovery and from its pages I went to other classic books that opened up a world of suggestions for me. And with these influences I started to write a story from the life of my grandmother Dolores, I regret that he was lost in so many comings and goings, in which I was interested in the character and his vision of the world that surrounded him. I have always felt losing that family story that made me face the fact of describing reality, although I have to confess that in full pandemic I thought about writing a delicious little novel, entitled The priest and the teacher, which takes place in 1936 and incorporates many of those things that my grandmother told me about.

Recognizing the success of this novel, which had to be reissued a week after it was released to bookstores, I must not hide that there have been failures, for example, when I started a novel about Ramiro II that I never finished and whose whereabouts I do not know, since I was already oriented to the world of archives and research. Which does not mean, far from it, that you cannot be a good novelist and a good historian and researcher. They both work with language and with the ability -maybe ability- to understand what the documents suggest or tell us.

- AL: A head writer? You can choose more than one and from all eras.

DB: I have always liked that prose of Azorin Through which you feel the landscapes of Castile, you get to hear the bells of the churches of the villages lying in the sun, you are moved by that silence of the afternoons with a siesta in the infinite plain that gave Don Quixote or Teresa de Jesús a landscape ... And I am passionate about the prose of Bécquer in which a world of imaginations, insecurities, sleeping fears within us is suggested, of memories that make us travel to the past and to the way in which the most remote villages of the Moncayo lived it.

It does not stop passionate me the cleaning of Machado's language, the beauty of the word as an instrument that suggests feelings. And of course I find it a delight Platero and me, which is nothing more than the attempt to make the most concrete universal, to make the harshness of daily living excellent, to understand that the closest and warmest silence can accompany us.

I'm a inveterate reader and I enjoy booksI have never stopped reading one that has started, although as life progresses you realize that time is limited and you must take advantage of it more selectively.

- AL: What character in a book would you have liked to meet and create?

DB: Like I just said, I love it Platero and me because I think it is a window to simplicity, to the authenticity of human beings. The words take on an image on its pages and all of them together are a declaration of peace with the world. Meet Platero, contemplate him, look at him. I would have liked to meet and create the characters of some Sender novels, as mosén Millán de Requiem for a Spanish farmer. And of course Duke Orsini of Bomarzo.

- AL: Any special hobby or habit when it comes to writing or reading?

DB: Silence and tranquility. I like that silence surrounds me because nothing should distract you on this trip to the past, because when I write I am in a distant century and I cannot get out of it. I can't hear voices from the present, nor the pounding sound of the cell phone dictatorially invading privacy. I like to start writing at the beginning and follow the order that the novel is going to have, I don't like jumps because the characters also lead you along paths that you had not decided on and, in the end, you rectify the path day by day. As I was saying, although I think about the plots walking down the street, traveling while I contemplate the landscape or about to fall asleep. I always write in the silence of the night and then I pass the resulting pages to my wife and daughter so that they can read them and make suggestions from their different points of view. A counterpoint of reality to the emotion of the writer is important.

- AL: And your preferred place and time to do it?

DB: I like to write. in my library, on my computer, surrounded by my books on the floor and with the notebook -sometimes a large empty agenda- in which I have been writing down the entire process of documenting the event to be novel. In its pages are the references of the readings made, the descriptions of the characters (the way I imagine them), the dates in which we move chapter by chapter, actually everything. Y I usually write at night, after twelve at night and until the wee hours of the morning because it is the moment of greatest tranquility, that time in which the experience of the night itself blurs the environment and it allows you to live in other times, even if it is only a psychological matter. It is that moment when you close your eyes and walk through Zaragoza in 1766 or through the city of Jaca in the cold winter of 1634 ...

- AL: Are there other genres that you like?

DB: I like to read. poetry, classic and modern, that relaxes me and makes me dream of scenes full of life. I enjoy with tests that allow us to get to know each other better. I am a fiery advocate of reading local historia, with which you learn a lot, and I am also passionate about the iconography treatises that teach you the language of the image. But, above all and since in my youth I discovered Amaya or the Basques in the XNUMXth centuryI am passionate about reading historical novel.

- AL: What are you reading now? And writing?

DB: I like to read almost everything that falls into my hands, but as I get older and as I indicated I put my attention on what I want to read, that interests me, that teaches me, that makes me dream. I'm not going to give names because I don't like to prioritize, everyone has their input and interest. What is clear is that I like to read historical novels, of which I have in my extensive library a very complete panorama of what is published in our country. There Aragonese authors are not lacking whose works I read as much as I can, although I am also honored to be able to read originals that some friends ask me to read before editing.

And if now I have to talk about writing, along with the lectures that I like to prepare in detail or the articles that I cannot refuse to do, I must refer to two novels: one that I have finished. The portrait of Goya's mother and another that I have started on the convulsive origins of the construction of the cathedral of Jaca, in reality, the confrontation between the king and his brother the bishop, cheered by his sister the Countess Sancha. It is an exciting story because it is to delve into seeing how art can be born even in confrontation and how beauty leads to the enjoyment of the encounter. Although if I am honest and reveal a secret, half, I will tell you that I have been documenting for two years and in the summers advancing the writing of a novel about the incredible last five days of the life of an Aragonese king, benchmark of the European monarchs. I would tell you that I am extremely passionate about this company.

- AL: And finally, how do you think this moment of crisis that we are experiencing will be counted? Will the reality of our history always surpass fiction?

DB: Surely many of our novels from the past are already recounting similar moments to those that we now have to live, with other means and in other settings, but let's not forget that the human being is the same and has the same virtues and the same defects. And this protagonist is the one who is surpassing himself in his social projection with and against those around him, opening a world of experiences that may seem like fiction. When I write the dialogues for my novel about the human and intimate Goya, which I have just published, I am surprised because much of what the genius of painting says is a very precise assessment and criticism of our situation: the loss of freedom, the gap between those who govern and the governed, the enjoyment that human beings find in making others suffer, according to their possibilities ... History always teaches us because it has a vocation for the future.

However, I have to say that I am convinced that ours will be a time about which exciting novels will be written that will have nothing to do with those written today, because the analysis of the facts needs a temporal perspective. Anger should never carry the pen that paints the moments of life.